Fight club: Life after the Jeremy Kyle treatment

Troubled families come together and fight on the Jeremy Kyle Show. It has been described as 'human bear-baiting', but the programme itself makes great claims about the good it does. So what happens when the cameras stop rolling?

He's only trying to help... Photograph: ITV/Rex Features

Even if you have had a job, full-time and relentless, since 4 July 2005, you will be familiar with the Jeremy Kyle show. Apparently conceived in the image of the Jerry Springer show, the programme gets together a troubled family to have a fight on air. Occasionally, the conflict will be rooted in some outrageous Dickensian injustice, such as, "My dad ran off with my fiancee" or, "My brother stole my mother's life savings while she was cooking his tea." Very occasionally, it will be a tear-jerking story of child illness or similar, in which the sorrow is its own titillation and none of the guests is required to be a monster or get booed by the audience.

Generally, though, the argument will centre on a sad story about elemental human weakness: domestic violence, infidelity, hooliganism, antisocial behaviour, bad or nonexistent parenting. Underneath all that, almost always, there's drug abuse, alcoholism or mental illness, often all three, in what sociologists call "constellated disadvantage". There's always a villain and, while I haven't watched every episode, I think it's safe to say the people on it rarely walk off stage reconciled.

It has had its critics: in 2007, a Manchester district judge, Alan Berg, was required to pass sentence on a man who had head-butted his love rival on the show. He called the Jeremy Kyle experience "human bear-baiting" and continued, "These self-righteous individuals should be in the dock with you. They pretend there is some kind of virtue in putting out a show like this."

That pretence of virtue is almost worse than the programme itself: the show's psychologist, as well as various producers, make large claims about the good they do. They offer counselling, or they get people into rehab or, with their trusty lie detectors and DNA tests, they sow the seed of truth that blossoms into a happy, if complicated, family unit. Kyle – who started his career as a salesman, moved to local radio, then on to present Jezza's Confessions for Century FM, which seems to be where he got his appetite for shouting at people with problems – says he "believes the only way to solve a problem is through honesty and openness". He himself is not free from human weakness; he was addicted to gambling, which led to the disintegration of a very short marriage in 1990. His former wife said he stole thousands from her in the service of his habit, which he has now kicked. He says he has OCD and licks his mobile phone to see if it's clean, but that's by the by.

On the show's website are heartwarming stories of people who have rebuilt their lives thanks to Kyle's trusty sword of truth and extravagant aftercare. Even though it is impossible to imagine a family whose life would be improved by an inaccurate lie detector test result or even an accurate DNA test, followed by a load of shouting, it is possible, from a distance, to believe them. Maybe Solomons come in all shapes and sizes; maybe a righteous arbitrator, publicly declaiming who's good and who's bad, is just what a dysfunctional family needs to make it start functioning again.

With such a spirit of open-mindedness, I contacted the press office, to see if they could put me in touch with a couple of former guests. We spoke at length about the idea, and then silence – a total stonewall. That's pretty unusual: even shows that think of themselves as quite low-rent, such as Deal Or No Deal, still like attention. So I think these people know they're not doing a huge amount of good. But I don't think they realise how much harm they can do.

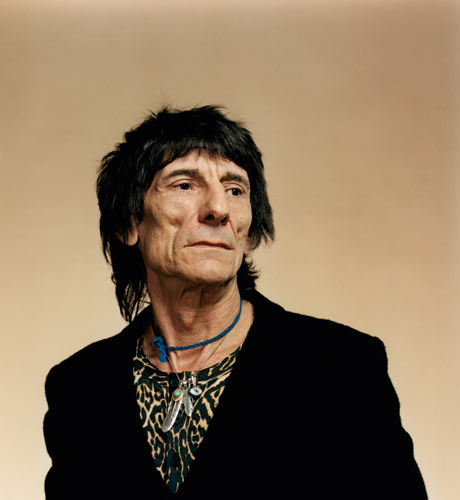

Chris Lyons with his mother, Andi. Photograph: Thom Atkinson

Chris Lyons with his mother, Andi. Photograph: Thom AtkinsonChris Lyons was 17 when he went on Jeremy Kyle, with Andi, his mother. They were living on the Isle of Wight; she was running a hotel with her now ex-husband and Chris was running amok, abusing drugs and solvents and customers. He applied to go on Trisha Goddard's show, which was soft and supportive and made apparently genuine offers of rehab. When Kyle replaced her, he took over her files, so producers contacted Andi and Chris and brought them to London (this was before the show moved to Manchester). They were put up in a hotel. Andi remembers: "When we got there, they kept calling both of us. Chris was up until two or three o'clock in the morning, talking to them."

I heard this from everyone I spoke to, bar one: they keep the families technically together, but functionally apart, with a researcher assigned to each, seemingly with the brief of winding them up (they weren't talking to them about current affairs, put it that way).

The next day, they were taken to the studio and put in separate rooms, where they say the baiting continued until it was time to go on. Chris says, "They kept coming in and saying, 'Your mum said this about you. Your mum said you were a dirty crackhead.' Some of the stuff they told me, I thought, 'My mum doesn't even talk like that, my mum would never say that.'"

I know this is obvious, and we probably realise this is how it works, but Jeremy Kyle has created the cultural spectre of this feral underclass, none of whom has the smallest amount of emotional restraint. That trope wouldn't exist without this programme. And I can't help wondering whatNewsnight would look like if all the guests were knackered from the night before and had spent hours in a green room, listening to researchers whispering, "You'll never guess what AC Grayling said about your book"; "David Aaronovitch called you a fat wanker."

For the show's part, a spokesperson says, "The Jeremy Kyle show has been on air for six years and is incredibly proud of its record in helping thousands of people across the country via a properly structured and resourced system of help and care for a wide range of issues and problems."

Anyway, Kyle seemed to decide, as the show started, that Chris's drug problems were actually Andi's fault. "Because I'd been married three times, he said, 'Any child would have problems after going through three marriages with you,'" she says. "But their dad died. He was making it sound like it was my fault their dad died."

Chris interjects: "I actually said at one point, 'This is really unfair on my mum.' And the audience clapped, they agreed." That bit was lost in the edit. So, they had the confrontation, Chris had a drug test, which came back negative ("He said, 'You're clear. Well done for that.' But I'd been on pills and coke two nights before, so I thought, your test's wrong"), Andi got shouted at, and afterwards there was half an hour of counselling.

One other thing: during the show, Kyle said to Chris, "Have you got a job?" "And I went, 'No.' He said, 'Do you want a job?' And I was like, 'Yeah, of course I want a job.' He said, 'Would you like a job working with me?' And I said, 'Yeah, of course.' Hang on, hear this: when they was filming it, he talked to someone on his earpiece and said, 'OK, we can do that, yes.' Then turned back to me and told me I'd be given a job as a runner."

Andi claims they received a letter two weeks later, saying the job was of course voluntary, no expenses would be paid, and "I've got to pay for somewhere for him to stay while he's up there," she says. "That's his idea of a job," Chris says, smiling. I find it hard to believe these two ever passed muster as the embodiment of broken Britain. They seem very understanding of, and kind to, one another. But Chris was taking a lot of solvents at the time.

They returned to the Isle of Wight. Andi was a bit embarrassed, but relatively unaffected, by the broadcast, but it was hard on Chris. "It ruined my life. All of a sudden, I wasn't Chris Lyons any more. I was just that guy off the Jeremy Kyle show." The producers asked him back for two more episodes, which he agreed to – one about problem teens, one on teen boot camp – though they never did get him any rehab, or give him a job. He did get half a day's unpaid work experience at a kennels.

Finally, Andi kicked Chris out, her marriage disintegrated and she moved to Croydon. Chris stayed on in the Isle of Wight, got off the drugs on his own, did some voluntary youth work and is now, at 22, living in Croydon and wondering what to do. "To tell you the truth, I haven't really got any ambitions," he says. "I wanted to be a soldier. But my lungs are completely shot from the time I was doing cans [solvents]."

Anthony Ghosh with his mother, Pat. Photograph: Thom Atkinson

Anthony Ghosh with his mother, Pat. Photograph: Thom AtkinsonOn the same show were Anthony Ghosh and his mother, Pat. They were, between them, a horse of a very different colour: Anthony was a "Bad Boy" (that was the show's title), but his misdemeanours were all sexual. He visited prostitutes, went to swingers' parties, paraded alarming sexual availability (at one point he was handing out business cards to the audience, I think with the basic message that he would sleep with any of them as long as they were female). You name it, as long as it wasn't regular sex with a long-term girlfriend, then he had either done it or claimed he had.

Ghosh, who also likes to be called DJ Talent, is perhaps an even more poignant example of the baffling complexity of most human conflict. Like Chris, he'd applied to go on Trisha, but not for help – he wanted to be famous. He's been on loads of reality TV shows; indeed, he is much better known for his appearance on Britain's Got Talent than he is for the Jeremy Kyle show (he did a rap that goes: "I say Britain/You say Talent/Britain's got talent!/It's the DJ Talent!"). Pat agreed to go on with him because, she says, "It's nothing to be proud of, sleeping with prostitutes. I found it very upsetting. I was hoping it would make him change." So they had pretty different aims from the start. Anthony chips in: "They played me off against my mother, and separated us when we got to the studio. They kept saying, 'Make a hard-hitting show and you could be a superstar. This could be your big break. But you've got to make television.'" Which he dutifully did.

"The way I remembered it, it was fun," he says. "But the way they cut it, it was very dark. It made me look like a bad person. And afterwards, watching it... It was all these strangers, angry strangers." Then his mood lifts a bit: "But I got my image exposed there and I got known in the media for having gold teeth and gold jewellery."

Pat carries on, tentatively: "Afterwards, they were hinting to me that they thought Anthony had manic depression, because of the way he'd been on the show. I didn't want to say anything to them, but I don't lie to people." Pat looks at Anthony, as if they've had a conversation, but she's not sure what they've decided; then looks at me, as if there's something she doesn't want to say but I should be able to guess. "I didn't say to them, he has bipolar. But I said, 'He is having treatment for something like that.'" Anthony takes up this story. "They'd said before we filmed it, 'Do you have any health problems?' and I said, 'No' because I didn't want it to count against me and I didn't want people in show business to discriminate against me. So after they'd spoken to my mum, they said, 'If we'd known, we wouldn't have had you on the show.'" But seeing the show aired two months later was much more of a shock than Anthony had been expecting. "I felt like everybody was looking at me wherever I went. So I just stayed in for a couple of weeks. And then I went to Eastbourne, because I've got a holiday house there. People were giving me dirty looks on the bus. I couldn't walk through the streets in Hastings. I felt attacked."

This hasn't dented his long-term goal of getting famous, though. In fact, he approached the show, wanting to go on again. I didn't really get to the bottom of the rationale behind this, but they turned him down for a second appearance, and he told them he felt they'd used him. A producer replied: "You've just had a quarter of a million pounds' worth of television made about your life." (I've been trying to work out how on earth it would cost a quarter of a million pounds to make a Jeremy Kyle programme for which none of the guests get paid, and I can only assume the producer must have been factoring in Kyle's own salary. The brass neck of these people!)

Anyway, Ghosh nurses certain sour feelings about Jeremy Kyle – he wrote a rap about it, in fact, sampling Kyle on the show, shouting at him. "I didn't sell the record. I just sampled him to make a fool out of him. And I did make a fool out of him." Finally, though, he feels that it got him where he wanted to be – "I got let down by Piers Morgan as well, he promised me a record deal. I think they're all out for their own egos, to be honest. But once you've achieved a Wikipedia page, you've got interviews on big programmes... My name wouldn't be out there if it wasn't for programmes like that."

He pauses. "It's taken me a long time to come out about my bipolar. I kept it a dark secret. But it educates people." He pauses again. "Do you think people will discriminate against me, because I've come out about it?" I honestly don't know, but I say, "No, I'm sure they wouldn't." "They wouldn't, would they? You'd have Stephen Fry on your programme."

Douglas Naylor. Photograph: Thom Atkinson

Douglas Naylor. Photograph: Thom AtkinsonDouglas Naylor was nothing like so vulnerable when he appeared on the show, to be the voice of hooliganism. He was in his 30s, he'd co-written a book and was in stable, if very specialised, work.

Naylor is a handsome guy, though there's something up with his face that I can't put my finger on. I meet him at a pub opposite Sheffield station. His daughter is with him, but she sits away from us, at the bar, with a friend. She looks sleek, young and successful, and I can tell she really wishes her dad wasn't doing this interview. She's eyeing him as if he's someone who habitually does a regrettable thing.

Naylor was invited on to the Jeremy Kyle show in 2006, pitched against the parents of a Leeds fan who had been killed in Istanbul in 2000. He says he didn't know that before he went on. He thought he was being invited on as co-author of Flying With The Owls: Crime Squad, a book about football violence, written from the point of view that it is a legitimate, fun hobby (it's full of lines such as: "A big scar-faced lad came my way. I caught him a nice one on the jaw, but was suddenly jumped on from behind", interspersed with a trainspottery precision: "Over the years I visited most of the bigger London grounds. At the time of writing, though, I have not been to Brentford").

Anyway, look, he's no angel. "Well, basically, I am a thug," he says. "But within reason. I would never attack someone unreasonably. My football thing was proper organised stuff with gangs. That was what I was brought up with, since I were a little lad. [Kyle] was trying to portray me as a football hooligan; I have been out to matches and I have had trouble with people, but I've never been one to bully anybody. I'll have a fight with like-minded souls."

So the show was vexing – but its impact, of course, came later. "They said I was a football hooligan, going to Germany [for the World Cup] to cause trouble. It was the worst impression they could possibly have given. Weeks after the show, I was going to Germany, I'd got flights, I'd got car hire... I got deported. CID followed me all the way to Dusseldorf, about 20 of them, some with guns. I got to passport control and they didn't even look at my passporit, they just handed it straight to the police and I were locked up, I were gone." I suppose that's life when you're on the record as a football hooligan. He was known to the police already, before the show. "But only to Sheffield police."

Following the programme, he was issued a banning order from Sheffield Wednesday's ground, with a three-mile exclusion zone. He says the police actually tried to issue his girlfriend with the same order, but that turned out to be unviable, because she hadn't done anything. And also she worked there. Naylor was fired from his job, as a sort of freestyling tree surgeon (I'm not sure what the technical term is, but he would undertake dangerous operations, shifting branches that had fallen on to power lines, with minimal precaution). "They wouldn't say they'd fired me for going on the show. But they fired me for one mistake. I made one mistake, after a whole career in it."

I'd say he has quite a high-risk personality, but he's not an obvious candidate for the vaunted Kyle aftercare, even if it did ever materialise.

Did they offer him counselling? "Well, a criminologist spoke to me afterwards. But he wanted me to come and do a lecture at his university [Leicester]. So I ended up on the university lecture circuit for a bit, describing the hooligan mindset to criminology and psychology students."

So it wasn't all bad? "No. Not until I was nearly killed." The hooligan dynamic here is interesting: there was a feeling among Sheffield United fans that Naylor had overstated his role in the Wednesday Firm and was actually a "nondescript" (this sounds mild, but is a very profound insult in the culture of fighting for fun). "Before I knew what was happening, I were the most famous thug in England. There are only certain places I can go without getting into a fight."

This notoriety, coupled with bad luck, landed him in a horrific fight: just him against a pub full of Sheffield United fans. Someone hit him with a lump hammer. When he arrived at hospital, he was technically dead and had to be resuscitated twice. One of his eyes is lower than the other now, but it's quite subtle. You'd only know if he told you.

He doesn't bear any ill will towards the Jeremy Kyle show, even if he is quite dismissive of the man himself. "It were a bad time in my life as well. I'd just split up with my wife, who I'd been married to for 17 years. I was more forward than I would have been. And nothing that happened was as bad as getting a divorce."

Robert Dunnill. Photograph: Thom Atkinson

Robert Dunnill. Photograph: Thom AtkinsonRobert Dunnill is the great success story of the Jeremy Kyle experience. He lives in Scarborough, looks both 10 years younger and older than he actually is (42), and his spick-and-span house is papered with photos of the Russian woman he met on the internet, whom he intends to marry. When I arrive, he has a video of the show he appeared on, back in 2005, waiting to go into the machine. We stand in his kitchen, watching it together. He seems to me to be almost paralysed with nerves on screen: pink, tongue-tied, exquisitely uncomfortable. But when I look at him standing beside me, I can see he's really pleased with the way it played out for him.

This is what happened: he met a girl, Sammy, on the seafront, took her home, and soon they were engaged. Opinion differs on the order of things, but they split up and she started going out with his dad, Frank. Robert's mother had died not very long before. After father and almost-daughter-in-law fell in love, they sold their story to various papers. One particular article, in Love It, was the final insult. "That were disgusting. I don't mind being famous, but when you look in a magazine and they're discussing being in bed, and how me dad were better than me. That's the part I didn't like. They were showing them having pillow fights."

Robert heard they'd made £1,000 from that one article. Quite fast, Frank and Sammy married and, on their wedding day, they told Robert that Sammy was pregnant. He was distraught. "It made it worse because I wanted kids with her. If me mam were here now, God help me dad."

At this point, he applied to go on the Jeremy Kyle show. And finally, he felt vindicated. It wasn't as if the public scrutiny was new, after all the media appearances his father and ex had made. The difference with the Jeremy Kyle show was that it told the world who was wrong and who was right. "They give me a lot of backing. And Jeremy Kyle himself was fantastic. At the end of the show, he shook my hand and told me, 'You did well there.' The crowd were booing her and booing him." During the programme, Jeremy Kyle delivers his trademark tirade at Frank, calling him the lowest of the low. You have to admit that he has a point.

Robert says the show gave him his dignity back; it was a huge relief, it took the stress out of the situation, it meant that people at work gave him more support, and it's been repeated 12 times now, so the world keeps on seeing how wronged he's been. "Before that, all me family were half with me and half with them. Because of Jeremy Kyle, they understood where I was coming from."

So that's how it works when it works. Some people need the validation of pure victimhood, and they deserve it – and then they're happy when they get it.

Terry Carvell. Photograph: Thom Atkinson

Terry Carvell. Photograph: Thom AtkinsonTerry Carvell's story is a lot more complicated. I heard only his account of events, but he was an alcoholic and a drug addict for 14 years, and spent those years in and out of prison, for violence and domestic violence. He and his wife, Allana, had a son who, he says, was taken into care because of the family's situation. Later, when Terry was in prison, Allana had a daughter taken away from her at birth, due to the family's history. In 2005, Allana applied to go on Jeremy Kyle with Terry, who was by then out of prison.

I met Terry in Milton Keynes, at his neighbour's house. He's slight, self-possessed, accommodating, quite fatalistic. He says that his wife (they're now separated, but not divorced) applied to go on the show because she wanted a night in a hotel, to meet Kyle and to see her cousin, who lived in Manchester. It seems likely, though, that she was also looking for redress after a catalogue of painful events.

Carvell, by the time the couple appeared, was clean of alcohol and most drugs, though he did still smoke weed. They arrived at the hotel, and say the night before was dominated by incendiary phone calls. The morning was spent winding them both up, and then, as filming commenced, came the show's pantomime of righteousness.

"To tell you how bad it was: I haven't spoken to anybody in my family for about the last 15 years, but even my family members who saw the programme wrote letters complaining about how badly he'd treated me, and that half of what he said was untrue," Carvell says. "We'd been recording for about 20 minutes or so and he said, 'Stand up, big man.' Well, I don't take crap from anybody. So I just looked at him. He got his microphone and he rammed it up under my chin. He was trying to provoke a reaction, and I just stood there. And he said, 'Just for one moment, you wanted to hit me, didn't you?'"

Aftercare amounted to a short debrief with Graham Stanier, the show's psychologist. (Terry already knew him: "It was a twist of fate, he used to be a psychologist at the detention centre I was at. Graham himself is a brilliant bloke.") They were offered counselling afterwards – three couples' sessions and three sessions of anger management for Terry alone. However, he says it was in Merseyside, 70 miles away from Blackpool, where they were living. "To be honest, I don't even know why they bothered saying it. Because there's no point offering assistance if it's going to cost you more than you've got."

So Terry and Allana returned home, the problems in their marriage unresolved by Kyle's therapeutic capers. Shortly after the show aired, Terry moved out. "I got my own flat in a different part of town. Mainly, it was about getting away from Allana." But also, Terry had perceived a hostile atmosphere on their housing estate, since the show had aired. "The area they moved me to was 90% alcoholics and drug addicts. They probably wouldn't even recognise themselves if they saw themselves on Jeremy Kyle, let alone anybody else. So I did feel a bit safer there."

Nevertheless, he decided to leave Blackpool and make a new life in North Wales. He says Allana, hearing about his plans, went with him, but left a note in her own flat for the police, saying he'd kidnapped her. It's true I have only his side of this story. But they were hitchhiking. His defence, that it's impossible to kidnap someone and hitchhike at the same time, seems quite convincing.

"We'd been in North Wales about four days when we saw all these police cars," he says. "I don't know what it was, sixth sense or something, maybe it was because there was so many of them. They always turn up heavy-handed for me because of my firearms history... Anyway, I don't know why, but I knew they were for me."

He says he was arrested and charged with kidnapping; the situation was resolved by the witness statement of a Christian DJ who'd given the couple a lift five days before. So Terry was released and they both – the relationship was quite resilient – moved to Scotland, together, whereupon they split again. Allana moved back to England and Terry lived in a tent for 18 months.

Does he think he would have ended up in a tent without the Jeremy Kyle show? "Yes. Most probably. Let's just say we had more chance of sorting our marriage out before we went on Jeremy Kyle. But I'm better off without her."