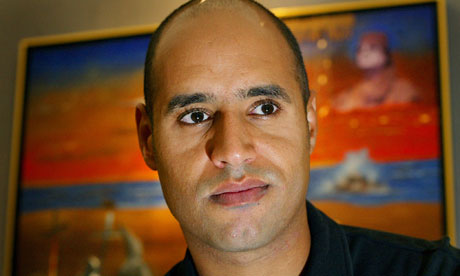

Saif Gaddafi: his father's son, or the would-be face of Libyan reform?

Analysts divided on motives of dictator's son who has emerged as key figure in negotiations

Saif Gaddafi in London in 2002. A former aide said he spent years trying to convince his father, Libyan president Muammar Gaddafi, to implement political reforms. Photograph: Kieran Doherty/Reuters

On 19 February Dr Muhammad al-Houni, a Libyan academic and long-time adviser to Colonel Muammar Gaddafi's son, Saif al-Islam, finished a speech he had written for his patron to deliver on state television in the midst of a crisis.

Four days into the Libyan uprising, Houni suggested Saif strike a conciliatory tone. He should apologise for those who had died in the country's east. He should insist too on the necessity of reforming his father's four-decades-old regime, announcing a tranche of long-promised laws to usher in new freedoms.

"I wrote down what he must say," Houni recalled on Thursday. "I said he should say sorry for the victims. But he went to his father and his father did not like it. So his father changed the speech."

When Saif appeared on television, he looked and sounded every inch his father's son, waving his finger angrily, and saying the words that have since become notorious: "We will fight until the last man, until the last woman, until the last bullet."

Houni left Tripoli the following day. Shortly afterwards he issued a furious open letter to his former employer, accusing Saif of "donning his father's cloak, which is contaminated with 40 years of his deeds".

Once regarded as the Gaddafi family's friendly, reform-minded western face, Saif, supported by his brother Saadi, has emerged in the past week as the most visible figure in the regime's efforts to negotiate an end to the conflict on its own terms.

One influential figure, who knows the regime and members of the Gaddafi family well, is convinced that Saif speaks for the family with his father's support.

"They are looking for a way out," said the source. "It makes sense forLibya if there is a good exit [for Gaddafi]. What I understand they are saying is that the sons want to continue playing a political role [after the regime has fallen] by having their own party.

"They would accept an interim government and a transition period. What they will not accept is being forced to leave the country. It is what Saif has been working [on]. It is about getting the sides to sit down together and talk and also about having an exit strategy that is not insulting to Gaddafi: that leaves him but without power. That's what Saif is fighting for."

It is precisely this plan, the source confirmed, that Muhammad Ismail, Saif's senior aide and fixer, is said to have presented during a confidential visit to London last month where he met British officials.

The proposal, however, has been rejected emphatically not only by Libya's rebels but by western governments – the UK prominent among them – which insist on the departure of Gaddafi and his sons.

But questions remain. Is Saif the bellicose son of a tyrant, the would-be reformer educated at the London School of Economics, or something in-between?

Houni believes Saif was in earnest about his desire to reform the regime, before he made the decision to adopt his father's hard line.

"It is complicated. Saif was serious. Now [after that speech] no one in Libya takes what he has to say seriously any more. No one will accept what he has to offer. He spent five years trying to bring about change but his father would not have it. He might want to talk about negotiations but it isn't possible."

Anger suffused Houni's open letter to Saif, in which he charged him with betrayal.

"I was at your side for over a decade," Houni wrote. "[Then] one unfortunate night, at one frightening moment, came that speech in which you threatened the Libyan people with civil war, the destruction of the oil industry, and the use of force to decide the battle. You chose your side in this conflict very clearly: you chose the side of lies."

Houni's argument that Saif was once serious about reform appears to be backed by other evidence, not least a leaked cable sent in 2009 by the then US ambassador to Libya, Gene Cretz, which discussed Saif's inner circle rejecting reports he might accept the position of "general co-ordinator" to which he was appointed by his father in early October on the grounds that he did not "want to be tainted by the current political environment".

In all the deeply opaque dynamics of power at the heart of Gaddafi's regime it is this, perhaps, that remains most hidden from view – the often dysfunctional relationships within Gaddafi's family and between the brothers. It is not just Saif's father who has been a stumbling block, Houni believes.

While Saif's brother Saadi has been supportive of him, he believes he faces opposition from three other sons: Hannibal, Khamis – who commands an elite military unit – and Moutassim, Libya's national security adviser.

Moutassim and Saif, in particular, are understood to have been fierce rivals for several years, not least over access to senior US administration officials.

While Houni is convinced that Saif did really once want change, others are sceptical about the entire reform agenda that Saif once championed.

Among those sceptics is Omar Ashour, an Egyptian academic who teaches on conflict resolution and Islamic radicalism at Exeter University.

A year ago Ashour was invited to Tripoli by Saif Gaddafi to speak at a conference. The theme was reform and a desire for reconciliation with some members of the regime's former foes in the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group.

"I was invited by Saif," Ashour said. "His proposal was to transform Libya by reforming education and the media and politics. His speech was all about reconciliation. What struck me, however, was not what he was saying but how he was openly opposed by other factions in the regime who did not want any reconciliation, who said: 'These people are the enemy.'"

Ashour has had a lot of time to think about what he saw in Tripoli a year ago and to make a judgment of the character and motives of Saif Gaddafi.

His conclusion, as Saif has emerged as one of the main movers in attempts to open negotiations for a ceasefire with the west to bring an end to the conflict in Libya, is an instructive one. For all Saif's talk about reform, Ashour is now convinced, the real issue has never been reform in its own right but rather a strategy for preserve the regime and his family's position at the head of it.

This week as the likelihood grew that the crisis would inevitably end in ceasefire talks, the problem of judging how to distinguish what Saif says from what he and his brothers want has become ever more acute.

"I think what I saw was a tactic for prolonging the life of the regime," recalls Ashour. "And Saif has only been able to speak the way he has about reform in the past because he has had the support of prominent figures in the internal security services, including Abdullah Senussi [the head of military intelligence] and Abdullah Mansour, while being engaged in a struggle with those opposed to any reform."

Which leaves a final and intriguing question: whether his long-offered promises of reform – which were always in the end blocked by other factions – created the conditions for the revolution against the Gaddafis in the first place.

Saif's talk of reform goes back to 2003. He had set a deadline – including 2008 for a new constitution – and promised new laws, 21 of them, which would have gone a large way to transforming the country. But not one of those laws has ever been put before the people's congress.

As recently as 14 months ago Saif was telling journalists that what Libyans needed most were open elections – "freedom like in Holland". Speaking last month to Time magazine, he had a different agenda, which perhaps reflected where he stands himself – distinct from his father and his brothers and the factions opposing him.

Then, what Saif wanted to talk about was not Libya's future but how he felt he had been betrayed by the hardliners, who blocked democratic reforms out of "stupidity" – and by his closest reformist allies who fled or joined the rebels.

He seemed unable to separate his family's future from the future of the Libyan people.

No comments:

Post a Comment