Gdansk's shipyard gets new wind in its sails as builder of specialist vessels

As the container ships leave, this symbolic home of the Solidarity movement is branching out into new ventures

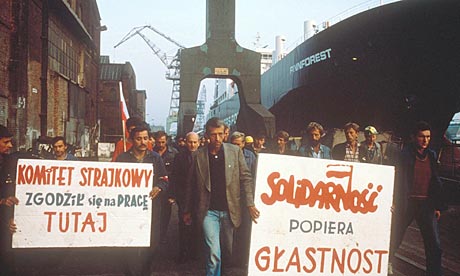

Solidarity demonstration at Gdansk Shipyard in 1988. Photograph: Sipa Press/Rex Features

On a windy afternoon at Gdansk Shipyard – the rallying point for the 1980s Solidarity movement which spelled the end of the communist regime – an 85-metre oil platform supply vessel slides off the slipway into the Baltic Sea. It is one of six specialist ships the yard builds every year, along with wind turbine towers.

Traditional shipbuilding has been history in Gdansk ever since the shipyard went bust in the 1990s, resulting in huge job losses. In the 1980s, when numerous tankers and trawlers were built in Gdansk, mainly for the Russian market, 40,000 people were employed in the shipbuilding industry. Today, that number has fallen to 10,000. Instead of big container ships, the shipyard is now building specialist vessels for oil rigs alongside luxury yachts for multimillionaires.

"We do not believe that we can compete with China or Korea on cargo vessels," said Arkadiusz Aszyk, a board member of Gdansk Shipyard, which is over 200 years old and built the fleet for Kaiser Wilhelm II. He adds: "We build more sophisticated vessels, and our clients in the offshore market are here in Europe or the US. We can see that in this niche market we can be competitive."

Gdansk Shipyard, now owned by a Ukrainian steel magnate, employs 1,700 people. It has also branched out into steel construction and is building the steel structure for the roof at Gdansk's new airport terminal.

The last state-owned shipyard in neighbouring Gdynia went bankrupt this week. After much restructuring, three big shipyards and 20 smaller ones are now left in Gdansk. One repairs and rebuilds ferries for companies like Stena. Another is a pioneer in wave energy plants for Denmark. A consortium of Gdansk shipyards is bidding for the lucrative contract to build a sea tunnel between Germany and Denmark.

The mayor of Gdansk, Paweł Adamowicz, a member of the centre-right Civic Platform party, has been accused of betraying the principles of Solidarity by pushing through a council housing reform to reduce the number of communal flats owned by the city, and sell them to private owners.

A local protest group, Nic o nas bez nas (nothing about us without us), says the reform will push up social rents by up to 150% and force many vulnerable people to live in "container houses" on the outskirts of Gdansk. Last month 500 people protested against the rent increases, led by the protest group.

Adamowicz says the city wants to increase the basic level of rent for everyone and then give discounts to the poorest. "It will be fairer, more transparent." The container houses are for antisocial people, he says, those who "drink too much and demolish their flats".

"We don't want to build a ghetto, but these tenants can't be evicted. We must provide flats for them by law," he added.

While a fresh wind is blowing through Gdansk, for some the changes are not happening quickly enough. Jake Jephcott, head of international development at Azo Digital, which makes energy efficient lighting control for streetlamps in London and elsewhere, says: "There is a war in trying to move things forward and to improve communication between the private and public sectors. We are in this battle, in between moving out of the old school and moving at the pace of the rest of Europe."

Gdansk is also building a financial services hub, but is behind other parts of the country such as Wroclaw in the west. The whole country is remodelling itself as a business services hub for international companies – from financial to customer services, human resources and IT – rather than a base for low-cost manufacturing, as it did in the 1990s.

However, Jerzy Stepien, deputy mayor of Poznan in western Poland, is worried that as salaries slowly go up, in a few years many companies could move on again to countries where labour is cheaper, such as Ukraine and maybe even Belarus.

No comments:

Post a Comment