With Tripoli's rebel underground

'They're going to catch me soon.' Libyan activist risks arrest to tell of guerrilla attacks and plans for suicide bombings

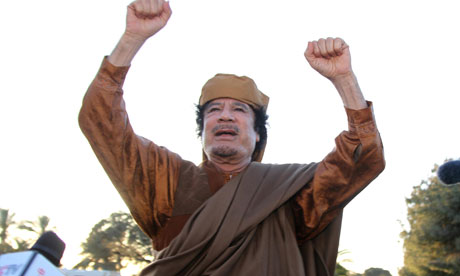

Rebels working undercover in Tripoli say Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi is their number one target. Photograph: Rex Features

He was rummaging in the boot of his car as we walked past. "Go forward," he instructed out of the side of his mouth. "I'll pick you up further on."

The car circled several times before he stopped. In a snatched conversation on the phone, he told us he feared he was being watched.

Eventually he felt confident enough to draw up. "You want to go to the fish market?" he called through the lowered window. "Get in."

No, we didn't want to go to the fish market, but as rare and highly-restricted westerners in Tripoli, we both needed a cover story for why we were getting in a Libyan's car.

Our contact was a middle-aged opposition activist in the heart ofMuammar Gaddafi's stronghold. Fear and danger are rife; the stakes are high.

During the course of an hour-long conversation, he told us that activists in Tripoli, frustrated by the violent suppression of peaceful protests, were now resorting to guerilla tactics to try to bring down the regime. Even suicide bombings were being considered, he said. His claims cannot be verified or properly evaluated, but they echo accounts obtained by other journalists in Tripoli, and help piece together a picture of underground opposition in the regime-held west of the country.

Our contact took us to a safe house some distance from the city centre. "I am not going to tell you my name, and I don't want to know yours," he said. Before we left, he insisted we delete his phone number from our mobiles.

"They are going to catch me soon," he said with a shrug. He suspected his neighbour of being a spy for the regime – "supergrass" the word he used, reflecting his years living in the UK.

"My name is on a list. Three or four of his boys are really interested in me." In the course of our discussion, he rarely called Gaddafi by name.

"My family don't know about what I'm doing – even my wife," he said. He and his fellow activists communicate using sim cards bought from migrant workers who have fled the country. They speak in code and rarely meet. They have "a few friends in Benghazi", the heart of the rebel-held east, with whom they are in sporadic contact.

Shortly after the Libyan uprising began in the east of the country in mid-February, activists in Tripoli attempted to mount a protest in the capital's central Green Square. It met a violent response from the regime. The rebels were forced to retreat and reconsider their tactics.

Now, the contact said, they were turning to guerrilla actions. They have attacked checkpoints across the city, killing the pro-Gaddafi militia and stealing their guns. The shooting that crackles across the city after dark, which regime officials claim is celebratory gunfire, is the work of the underground rebels, he said. "They [the regime] are covering up ... Every night there are attacks. The boys [on the checkpoints] have got scared. They are only getting 40 dinars (£20) a night, and they are saying we don't want to do this dirty work any more." There have been fewer checkpoints since the attacks began, he claimed.

Asked how they felt about killing fellow Libyans, he replied: "If we don't kill them, they're going to kill us."

The rebels, he said, were planning attacks on petrol stations. Fifteen police stations in the capital have been burned down since the uprising began, he said.

And the underground activists were preparing even bigger attacks. "People are ready for suicide bombings." He told us the rebels were gaining access to explosives from fishermen who use dynamite to stun or kill fish to aid harvesting.

The Libyan leader himself was their number one target, he said. How would they get near him? "We will. We can get near him."

He also claimed that Gaddafi, sooner or later, would face threats from within his inner circle. "People on his side are not with him 100%. They are waiting for one spark. We are waiting for one or two army commanders to turn against him. Then we've got him."

It is, of course, impossible to be certain of the credibility of what we were told. Reporters are denied free movement and access in the regime-held west of the country. But contacts made by other journalists in Tripoli have elicited similar information.

Reuters this week reported opposition activists in Tripoli as saying there have been several attacks on checkpoints and a police station in the past week. It quoted a Libyan rebel sympathiser living abroad but in daily contact with activists in the capital as saying: "There have been attacks by Tripoli people and a lot of people have been killed on the army side."

Other snatched conversations point to dissent rumbling beneath the surface. In a quiet alleyway in Tripoli's old city, a 33-year-old man said he had a rebel flag hidden at home, waiting for the day when Gaddafi goes. "I have a tricolour in my house, I will bring it out when we are free."

In a separate whispered exchange, a shopkeeper said: "Most people are against the system, but can't speak out." Another described Gaddafi as "stupid, a crazy guy, he killed many people".

Many underground rebels have died at the hands of regime forces or have disappeared, our activist contact said.

On 25 February, about 10 days after the uprising began, opposition activists took to the street after Friday prayers. "They were shooting straight away. Six or seven people at [one] mosque, eight at another. It's difficult to count. They pick up the bodies, then claim they were killed by the coalition [airstrikes].

"A lot of good boys are being arrested every day," he said. "They [regime forces] knock on the door. If it's not opened, they smash it down.

"They pick up whoever is in the house. They picked up eight from here three or four days ago. They take the people at night. Some have been held for 50 days."

It's impossible to find out what has happened to them or even to ask the authorities, he said. "If I get arrested, I don't want anyone to look for me because then they will be arrested too."

The youngerA man in the old city told us his cousin disappeared five days before our conversation. They came to his house and took him away, he said. "I can't even ask anyone where my cousin is, it's too dangerous." Thousands of people have disappeared in Tripoli since the crisis began, he claimed.

Figures are impossible to obtain. Amnesty has documented in detail around 30 cases, mainly in the east of the country, while Human Rights Watch has reported a wave of disappearances and arrests in the capital. Our activist contact estimated that a substantial proportion of Tripoli's population oppose Gaddafi. "50% are against him, 25% are on his side and the rest are scared," he said. "But as soon as things change, they'll change quick."

He rejected regime claims that al-Qaida is behind the Libyan uprising. "It's rubbish. He's lying. It's all bullshit, propaganda. This is a pure Libyan revolution. We don't rely on al-Qaida to do our job, Libyans do this."

He said he had high hopes of Nato intervention assisting the rebellion. "I was very happy. I cried when 1973 [the UN resolution authorising military action] was passed, I thought that's it. People were screaming with happiness." Now Nato was not doing enough.

Despite the opposition's struggle to gain ground in the east and the failure of the rebellion – as yet – to take firm hold in the west, the activists will not give up, he said. "They are not going to stop us. You can only die once." Was he prepared to die? "Yes. For our freedom."

No comments:

Post a Comment